A framework for financial bubbles

Patterns to understand, predict and navigate financial bubbles from Boom and Bust: A Global History of Financial Bubbles

We may be going through the biggest bubble since the Great Financial Crisis. In fact, we may soon have to navigate the greatest financial crisis in modern history.

On the other hand, we may be entering a period of accelerated economic growth. The adoption of AI, self-driving cars, automation and robotics along with regulatory streamlining and the acceleration of capital investment across the world may bring about a golden age.

How would you know, one way or the other?

The global economy works in cycles. Periods of expansion lead to market corrections and subsequent recoveries. Expansion. Correction. Recovery.

Understand these cycles—how they work, what they look like, what they feel like—and you can better predict where economic forces are moving. You can better navigate the tides where your personal circumstances meet the broader economy.

Or you can ignore these forces at your peril.

Predicting the dot-com crash saved PayPal

You might have heard of the PayPal mafia. The co-founders and early employees of PayPal went on to have a huge impact, first in Silicon Valley, and now all over the world. But before all that, they almost lost everything in the dot-com crash. They would have, if they hadn’t seen the crash coming.

PayPal emerged from the merger of X.com (Elon Musk) and Confinity (Peter Thiel and Max Levchin). The strategic rationale was to become the payments standard on the internet. Importantly, this allowed them to re-allocate precious resources they had been burning in a destructive war with each other. The most immediate problem was to figure out how to stop hemorrhaging cash before it was too late.

On March 30th, 2000, they announced the merger and a $100 million round of financing. The round optimized speed over valuation.

The crazed nature of it all confirmed Thiel’s suspicions about the market… “Peter kicked everyone’s asses to get that funding round done,” David Sacks remembered. Many Confinity employees—who had seen Thiel at his toughest—rarely remember him this insistent. “If we don’t get this money raised,” Howery recalled Thiel saying, “the whole company could blow up.”

Musk too anticipated an impending downturn. In mid-1999 he warned an interviewer… about a coming collapse. “Any change this profound is bound to set off speculative frenzy” …Musk predicted a reckoning. “This is the longest peacetime expansion in history,” Musk said. “And for young people who have never really seen a serious recession… the downturn will be a rough experience.”

- The Founders: The Story of PayPal and The Entrepreneurs Who Shaped Silicon Valley

If that’s not conviction enough, a couple of months later, Thiel took his doomsday prediction to its logical conclusion. In the summer of 2000, he made a proposal to the board:

“The markets,” he said, “weren’t done driving into the red.” He prophesied just how dire things would get—for both the company and for the world. Many had seen the bust as a mere short-term correction, but Thiel was convinced the optimists were wrong. In his view, the bubble was bigger than anyone had thought and hadn’t even begun to really burst yet… The company balance sheet could drop to zero with no options left to raise money. Thiel presented a solution: the company should take the $100 million closed in March and transfer it to his hedge fund, Thiel Capital. He would then use that money to short the public markets.

- The Founders: The Story of PayPal and The Entrepreneurs Who Shaped Silicon Valley

The board balked at this. They voted down the proposal. Of course, Thiel was right about the market and the NASDAQ proceeded to lose 70% of its value over the next two years.

Ultimately, eBay acquired PayPal for approximately $1.5 billion in October 2002. The founders and investors made tens of millions while saving a product that created substantial value for internet commerce at the time. Without the foresight to merge and raise capital before the bubble burst, PayPal would have likely gone bankrupt—as did many other dot com startups.

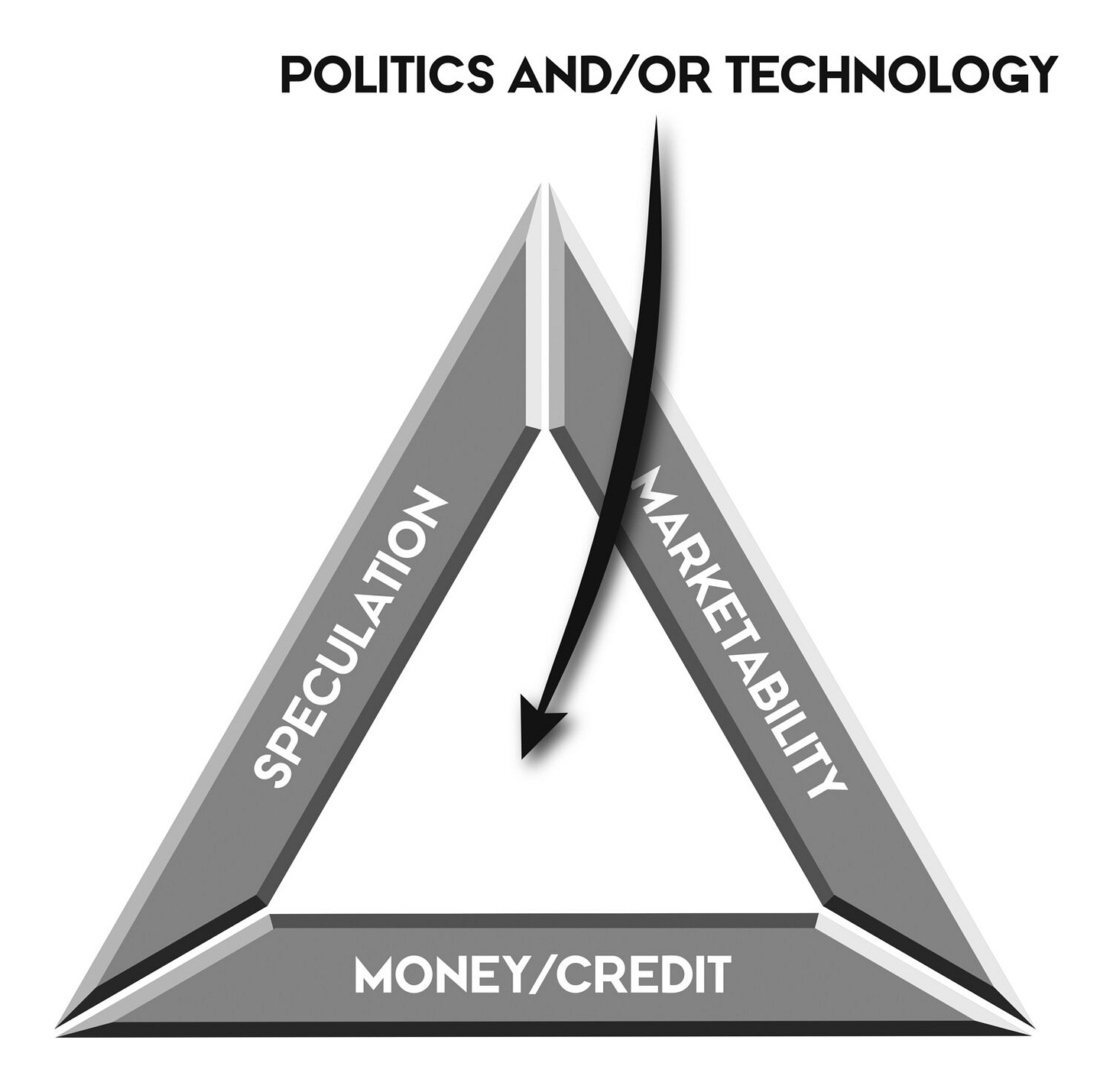

The wildfire triangle of financial markets

The book Boom and Bust: A Global History of Financial Bubbles lays out the basic structure of a market bubble as a triangle with three variables plus a spark. They use the metaphor of a fire.

Fires need fuel—dry wood works great. Fires need oxygen—regular air, check. Fires need heat—once they get going, they generate their own heat and become self-sustaining. Fires need a spark—an initial energy boost to activate the reaction.

Bubbles need money and credit—investment dollars that flow to the bubble asset. Bubbles need marketability—easy ways to buy and sell the asset. Bubbles need speculation—energy from market participants betting on asset prices to rise quickly. Bubbles need a spark—an initial energy boost to activate the speculative frenzy.

Money and credit as fuel

In order for a bubble to form, there must be abundant money and credit. Without it, the market lacks sufficient fuel to light a fire. There must be ample financial capital looking for investments.

Financial capital might increase as individuals reap the benefits of fiscal policy—lower taxes, stimulus checks. It might increase from changes in monetary and credit policy—lower interest rates, looser credit standards.

Changes in credit can increase the availability of financial capital substantially as investors borrow money to invest. This can be compounded when credit is ample and interest rates are low because investors can increase leverage to amplify returns while capital reaches for yield in riskier assets.

Using credit to fund investments also shifts the downside risk from the principal making the investment decision to his lender. The more leverage, the more powerful this dynamic.

Unlike real fires, the bubble can create additional fuel for itself as asset prices rise. As the bubble inflates, it creates additional money in the form of appreciation. Moreover, the additional money is already in the hands of willing market participants.

During the early 1990s, the shift from defined benefit plans like pensions towards defined contribution plans like 401(k)s contributed a substantial increase in the amount of capital available for investment in equity markets. Moreover, in 1992 the Fed lowered rates to their lowest level since the 1960s.

This combination contributed significant fuel to the dot-com and telecom bubbles.

Marketability as oxygen

In order for an asset to experience a bubble, it must be easy to buy and sell it. Ease of access is crucial for the bubble to reach critical mass.

Assets that are divisible into smaller units are better candidates for bubbles precisely because they are easier to buy and sell. It’s easier to transact on a single share of a company, which represents fractional ownership, than to buy a house. Unless of course… someone securitizes mortgages, in which case, houses can become a bubble asset too.

It’s also easier to create a deep pool of buyers and sellers for assets that are broadly available and easy to transfer. It’s easier to buy bitcoin, a digital asset broadly available for anyone to buy, than rare art, a physical asset with extremely limited supply.

Sometimes marketability can increase substantially because of deregulation, financial engineering, or legalization.

For instance, the combination of a financial innovation—new ways to pool mortgages into collateralized mortgage obligations—and a legislative change—The Secondary Mortgage Market Enhancement Act of 1984—unlocked the market for mortgage-backed securities that would balloon in the 90s and, among other forces, ultimately led to the Great Financial Crisis in 2008.

Speculation as heat

While money, credit, and marketability are pre-requisites to a financial bubble, speculative energy from market participants is needed to sustain one. Arguably, markets always have a degree of speculation. In bubbles, however, speculation dominates pricing dynamics—particularly speculation that an asset’s price will rise in the near future.

Early participants make profits as the asset price rises. This encourages additional entrants. Some are seeking profits. Others fear they might miss out.

Novices enter the market. Participants trade on momentum—that is, as prices rise, the expectation that they will continue to rise, itself drives prices higher.

The bubble becomes self-sustaining.

In the mid 1710s, Isaac Newtown invested early in the South Sea Company, which had a monopoly on trade with South America. He wisely sold as share prices increased to frenzy levels in April 1720 earning a substantial profit. However, as the bubble continued to inflate and Newton watched others reaping massive profits, he re-entered the market aggressively months before the bubble burst.

“I can calculate the motions of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.”

- Isaac Newton

In the beginning, there was a spark…

There are two sources of sparks, each of which can ignite a bubble. Oftentimes, these two combine to provide the activation energy for a bubble to inflate.

Technological innovation

The development of a new technology can inject enough energy into financial markets to set off a frenzy. A new tool or process that solves a problem in a substantially better way can set off fireworks in market participants’ imaginations.

The company that brings the technology to market might show abnormal profits or growth. This typically translates to significant gains in the company’s value, which itself attracts momentum traders.

Companies that use the new technology (or who claim to) go public or raise capital. Some might promote huge windfalls just around the corner.

Valuations start to levitate well-beyond what the fundamentals imply. They persist because the technology is new and its impact is uncertain. There may be limited data for a complete valuation. The focus shifts to metrics beyond traditional profits and cash flow.

Excitement from market participants leads to media attention, which fans the flames. There’s often a “new era” narrative insinuating that traditional valuation metrics may be obsolete.

Speculation feeds on momentum, which drives more speculation leading to ever higher prices.

Government policy

This is pretty straight forward. Sometimes governments change policies, and that creates intense market forces in a specific direction.

Sometimes this is related to legislation that impacts a specific asset. Most often, this plays out as broader macro policy changes that create the conditions for a bubble to form.

The most prominent levers in this category are:

A reduction in interest rates

An increase in the money supply

Broad financial deregulation

Deregulation might lead to looser credit standards and increase the availability of credit. It might also make it easier to buy and sell certain assets thus increasing marketability.

How bubbles burst, sometimes catastrophically

Bubbles are Shakespearian dramas masquerading as Homeric epics. In the 1926 Hemingway book, The Sun Also Rises, a character named Mike Campbell is asked how he went bankrupt, and he responds: "Two ways. Gradually and then suddenly."

The beginning of the end for bubbles occurs when they run out of fuel—money and credit. This is almost inevitable because there are limited amounts of capital available to invest in bubble assets.

The most common way for capital to start drying up is a rise in interest rates or tighter credit, or both at the same time.

A rise in interest rates makes borrowing more expensive thus reducing credit. It also adds safer alternatives from which to generate yield.

Tighter credit standards prevent market participants from rolling over their debts. More importantly, it might force them to liquidate assets in order to pay debts back. That in turn may drive asset prices lower reversing momentum.

These shifts in money and credit can trigger a sell off that becomes self-reinforcing in the opposite direction. Momentum takes off and participants might sell precisely because the price is dropping.

At that point, the crash is practically guaranteed.

The resulting damage depends on the size of the bubble, or more importantly, how central the bubble asset is to the broader economy. If the two combine—that is, a substantial percent of financial capital is invested in a bubble asset that has become deeply integrated with the rest of the economy—the crash can be catastrophic.

Deep integration may come from supply chains. Industries with deeply integrated supply chains experience a cascade of failures. A failing company’s canceled purchases are the source of another’s revenue.

Deep integration in the banking system is the nuclear scenario. Every other type of integration pails in comparison. The failure of a bank can create doubt about other banks. This might lead to a bank run—depositors rushing to cash out before the bank collapses. It might also lead to a stock market crash if investors rush to the safety of safer or more liquid assets. This dynamic may force down the value of the banks’ assets leading to a snowball effect that takes out chunks of the economy in an avalanche that creates scenarios like the Great Depression.

At worst, the failed bank might lack enough value to fund its obligations thus amplifying the impact across its counterparties, depositors, and investors. At best, the failed bank generates uncertainty triggering panic across other market participants. A rush for the exits ensues and the economy gets trampled.

Systemic bank failures are economic catastrophes of biblical proportions. Incredibly interesting to study. Terrifying to live through.

If you understand how bubbles work, you might just be prepared for the next one.