The basics of global trade

Before you try to understand the market's reaction to the White House announcement on tariffs, you need to understand global trade

Markets retreated following the White House’s tariff announcement on Thursday. They tumbled further as China and others announced retaliatory tariffs.

All major stock market indices are down double-digits since February and credit spreads widened sharply.

There are multiple variables playing out. It’s not just the tariff announcement, but what the tariff announcement means for the future. Stocks are priced based on future expectations.

Coming into this year, market prices reflected optimism about productivity gains and economic growth.

Government deregulation would unlock it. Technology would drive it.

That vision was called into question when the White House unveiled their proposed tariffs. Before you try to understand what the market is reacting to, you first have to understand the basics of global trade.

Trade 101

Simply put, global trade is the exchange of goods and services between countries.

Consider the most basic example in economics. Suppose I have two oranges, and you have two apples. I would like an apple and you would like an orange.

If we barter with each other—I give you an orange in exchange for getting one of your apples—we’re both better off.

Now suppose that I don’t have any oranges to give you but I still want an apple. We need some medium of exchange—some sort of token, or money—that you would value just as much as my orange. Money that you might use to get the orange from someone else.

Let’s call this money the “dollar”. If you could buy an orange from someone else for one dollar, you might agree to sell me one of your apples for one dollar.

Introducing money makes transactions much easier. We don’t have to match preferences to barter. Instead, we establish a price in dollar terms. As long as there are lots of producers to trade with, I don’t have to produce everything myself and I don’t have to find someone who matches my preferences perfectly.

Extrapolate that to the global economy, and you’re almost there--with one critical exception. What happens if you can’t use the dollar I paid you to buy what you need? Or more importantly, to pay your taxes?

Trade and Capital Flows

When a US company buys goods from a company in another country, it pays in dollars. The US company trades its dollars for Foreign-Co’s goods.

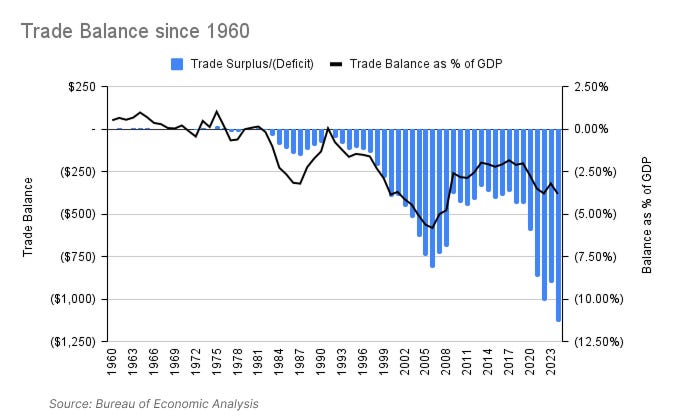

The US does that a lot actually. With the exception of 1991, the US has bought more from abroad than it has sold every year since 1982 (Figure 1). That’s dollars going out to pay for goods and services coming in—a trade deficit.

However, dollars are not legal tender outside the US, so Foreign-Co trades the dollars it receives to its local currency. Those dollars go to (i) someone who buys assets in the US (stocks, bonds, property), or (ii) a US bank account where the bank lends them out to someone in the US.

That means dollars that flow out of the US as part of a trade deficit flow back into the US as investment.

To understand the implications of this, you should be familiar with what economists call the National Savings and Investment Identity.

Supply of financial capital = Demand for financial capital

Domestic savings + Foreign capital inflows = Domestic investment + Government borrowing

In other words, the financial capital available in an economy comes from two sources: domestic savings—money in savings accounts, 401k’s, pensions, endowments, IRAs, and yes, even your Robinhood account—and foreign capital inflows. This financial capital funds domestic investment and government borrowing.

The equation has to balance.

Cause or Effect?

The National Savings and Investment Identity gives you an idea of where trade deficits come from. Large trade deficits are matched by large inflows of foreign capital. As inflows of foreign capital increase, the other variables must move for the equation to balance.

For example, if total investment stays the same, domestic savings would need to decrease to accommodate higher inflows of foreign capital.

Alternatively, if domestic savings stay the same, then three things can happen to accommodate more inflows of foreign capital

Domestic investments might increase

Government borrowing might increase

The cost of capital might decrease, or said differently, asset prices might rise while borrowing costs fall

Of course, all these could also move simultaneously to accommodate the higher inflows of foreign capital.

An interesting question to ask is, do trade deficits increase inflows of foreign capital? Or, do inflows of foreign capital lead to higher trade deficits?

It’s complicated.

All these variables are a two-way street. That is, changes in one variable influence the other variables, which in turn influences the original variable. And so on.

Moreover, there are other variables that influence trade dynamics—the availability and cost of labor to manufacture goods in a given country, for instance; or more importantly, the relative strength of a given country’s currency against the dollar (more on this shortly).

In order to understand how these dynamics have played out historically in the US, you need to know three things.

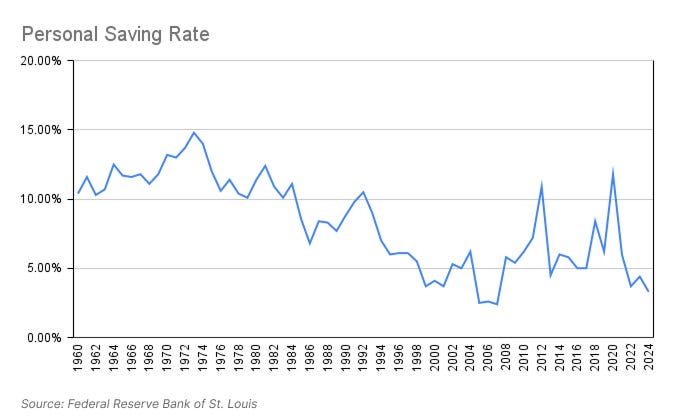

First, the personal saving rate in the US has been on a downward trend for years (Figure 2). That means domestic savings has been low and declining for decades.

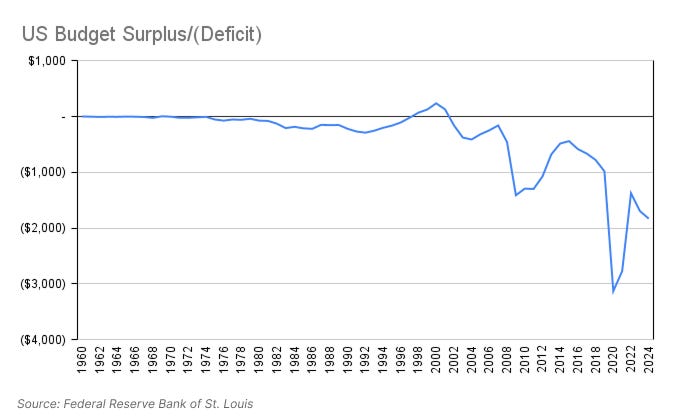

Second, the US government has run a budget deficit every year since 2002—a trend that dipped with the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, improved during the recovery, then reversed in 2016 (increase in entitlement spending, interest expense, and tax cuts), and accelerated with the pandemic in 2020 (Figure 3). That means government borrowing from large budget deficits has been growing for decades.

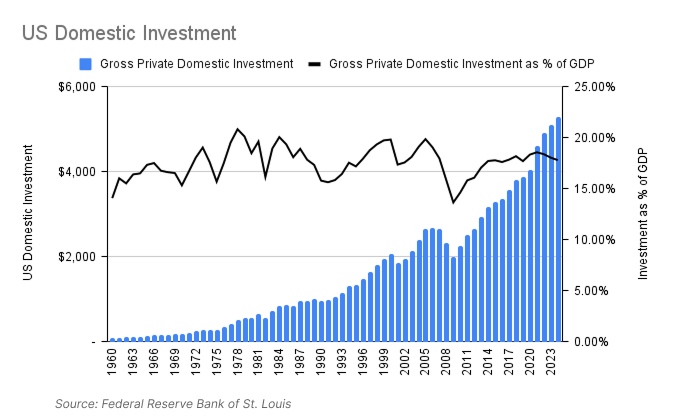

Third, domestic investment has kept pace with the economy (Gross Domestic Product, or GDP). You can tell because investment as a % of GDP has been remarkably consistent for decades at around 17.5% (Figure 4). That means domestic investment has been growing at a very healthy rate.

To put it all together, the right side of the equation—domestic investment and government borrowing—has grown substantially every year. On the left side of the equation however, domestic savings have been low and declining.

The only way to bridge that gap—that is, meet the increasing demand for capital—is with inflows of foreign capital. And there’s plenty of demand for US assets.

Reserve Status

While dollars aren’t legal tender outside the US, the dollar is the world’s reserve currency. This means that other countries use dollars to price assets and trade with each other—even when the US isn’t involved.1

88% of foreign exchange transactions and 54% of global trade is done in dollars.2 Companies and governments need to hold dollars in order to execute transactions. These dollars are typically held in the form of US Treasuries and other dollar-denominated assets to earn interest.

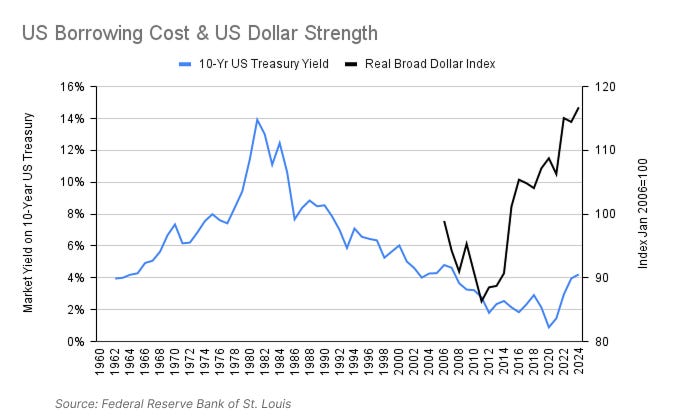

This extra demand for dollars has two critical consequences: it allows the US to borrow at lower rates than it otherwise could, and it keeps the dollar strong against other currencies (Figure 5).

A strong dollar means US consumers can buy goods from other countries at lower relative prices. It’s as if your apple sells for one dollar in your neighborhood, but I have special dollars that are the equivalent of two of your dollars. In effect, I can buy your apple for what, to you is a dollar, and to me is actually half a dollar.3

A strong dollar makes imports cheaper for the US, while making US exports more expensive for other countries. This dynamic widens the trade deficit.

Foreign demand for US assets means inflows of foreign capital. Those inflows, among other things, keep the dollar strong relative to other currencies. That, in turn, makes imports to the US cheaper and exports from the US more expensive. Thus, the reserve currency status of the dollar adds pressure to the trade deficit.

Everything Else

There’s a lot more to what’s been playing out in the markets that goes well beyond the realization that trade deficits have been financing US investments and government borrowing for decades—things like inflation expectations, exchange rates, recession fears, deglobalization uncertainty, trust in US markets—all critical to consider.

Understanding the basics of global trade and capital flows, is a prerequisite to understanding everything else.

The dollar is the reserve currency largely due to economic forces. At a high level, a global reserve currency needs to be stable, backed by a large domestic economy, and be tied to stable macroeconomic conditions subject to the rule of law.

The dollar has been the leading reserve currency since World War II. There are substantial debates going on as to whether this is sustainable. For more information, check out the Atlantic Council’s Dollar Dominance Monitor.

This is illustrative and overly simplistic. Exchange rates fluctuate and the difference between major currencies isn’t quite as dramatic as this scenario implies, but you get the point.